Bódy Gábor The most outstanding in European cinema of the 70s and 80s

Magyarul |

A source of interesting discoveries

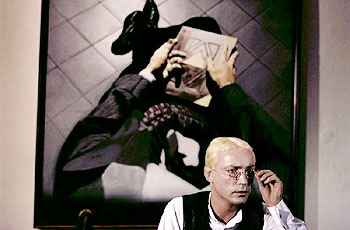

BÓDY Gábor (1946–1985) is one of the most outstanding and unusual personalities from the Hungarian and European cinema of the 70s and 80s – multi-sided, fascinating and dazzling. He belongs to the group of radical and most daring innovators of our time.

BÓDY Gábor (1946–1985) is one of the most outstanding and unusual personalities from the Hungarian and European cinema of the 70s and 80s – multi-sided, fascinating and dazzling. He belongs to the group of radical and most daring innovators of our time.

In the 80s, a widespread interest for BÓDY Gábor’s work arose, following the repercussions around his second feature film “Narcissus and Psyche” (80) which spread particularly in the movement of independent and avant-garde cinema. But also through his many other activities, his lectures, video works, installations and tours BÓDY Gábor became a universal source of inspiration and ideas among filmmakers and film lovers.

After his untimely death in 1985 (BÓDY Gábor was just 39 years old), BÓDY’s films passed into oblivion, and today his work, which is rarely mentioned in film literature, has become the object of secret recommendations; only few cinema goers of the younger generation will know his name. However: BÓDY’s films, in the light of new cinema developments, are a source of interesting discoveries and revelations for our present epoch. Therefore it appears useful and necessary to discover his films anew, to think about them, to examine BÓDY’s theory and practice. This is also and especially true for a country like Japan. Dealing with BÓDY Gábor’s work will open up a chapter of European film history (between East and West) and shed light on the international avant-garde movement – to which BÓDY Gábor certainly belongs.

Background: cinema matters in Hungary

BÓDY’s films were made in a country and at a time when in Hungary as well as in the other countries under communist domination, all cinema matters were subjected to a strict control by party officials. Cinema was considered an art for the masses which should exercise a political influence and therefore was put under severe regulations; so that experimental or subversive films had almost no chance to be made at all. It is true that cultural politics in Hungary were somewhat more liberal than in other countries of the Eastern block, but even in Hungary the film artists were under close surveillance so that a temperament like BÓDY found it difficult to put his ideas into practice.

But luckily there were some – at least temporary – niches and free spaces for artists like BÓDY Gábor, among them the “Studio Bela Balazs” (established already in 1959 and named after the Hungarian scriptwriter, critic and theoretician) where short and experimental films, later also full length feature films could be made in an atmosphere of relative liberty. The Studio Bela Balazs was a meeting place for the most gifted authors and directors of Hungarian cinema. BÓDY Gábor joined the studio as early as 1971, in 1973 he established, inside the studio, the “experimental film group K3” as a platform for true experiments.

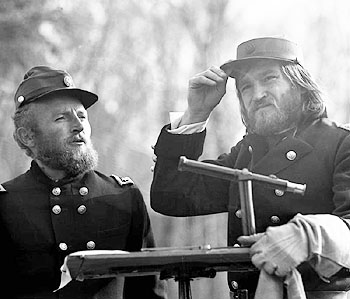

“American Postcard”

(aka American Torso)

From 1971 to 1975 he studied film direction at the Hungarian film academy. His diploma film was “American Postcard” which immediately after its completion in 1975 created many echoes and won the main award at the Mannheim Film festival (Germany) in 1976. The film tells the story of three Hungarian officers who serve as land surveyors during the American Civil War. The film makes use of authentic diaries, of a text by Karl MARX, of poems by Walt WHITMAN and of a short story by Ambrose BIERCE. “American Postcard” was a real experimental movie (maybe for the first time in the Eastern Block). BÓDY was experimenting with (a method of blending one scene into the other by a slow fade into white), he was using masks and inserts (frequently the camera looks through a telescope); in some moments of the film he tears up the film material and makes it dissolve. The film was really dealing, beyond the narrative line, with the subject of film language itself; the activities of the land surveyors appear as a metaphor for the process of making a film. Through the manipulation of space and time, BÓDY conferred an archaic and, at the same time, poetic quality to the images of his film. The subject of emigration, of liberty and independence also played an important role in the film.

From 1971 to 1975 he studied film direction at the Hungarian film academy. His diploma film was “American Postcard” which immediately after its completion in 1975 created many echoes and won the main award at the Mannheim Film festival (Germany) in 1976. The film tells the story of three Hungarian officers who serve as land surveyors during the American Civil War. The film makes use of authentic diaries, of a text by Karl MARX, of poems by Walt WHITMAN and of a short story by Ambrose BIERCE. “American Postcard” was a real experimental movie (maybe for the first time in the Eastern Block). BÓDY was experimenting with (a method of blending one scene into the other by a slow fade into white), he was using masks and inserts (frequently the camera looks through a telescope); in some moments of the film he tears up the film material and makes it dissolve. The film was really dealing, beyond the narrative line, with the subject of film language itself; the activities of the land surveyors appear as a metaphor for the process of making a film. Through the manipulation of space and time, BÓDY conferred an archaic and, at the same time, poetic quality to the images of his film. The subject of emigration, of liberty and independence also played an important role in the film.

“Narcissus and Psyche”

But the most ingenious and sensational film by BÓDY Gábor was without doubt “Narcissus and Psyche” (80). This film which exists in three different versions, the longest of which lasts three hours and forty minutes, is an overflowing, romantic and operatic story of love and doom, interrupted by lightnings of passion and sudden visions, embroidered with stylized visuals and surreal exaggerations, a cataract of images, camera movements and double exposures, but also of exquisite landscapes, architectural sights and angles. The story of the film moves over a time span of over one hundred years (beginning before 1800 and ending around 1920), during which the protagonists do not age at all. Behind the narrative line, the European history of the 19th century becomes visible, a process of dissolution and decomposition of the bourgeoisie as well as the nobility. In one scene, a telephone is picked up and from the earpiece a voice can be heard which strongly resembles that of Adolf HITLER.

But the most ingenious and sensational film by BÓDY Gábor was without doubt “Narcissus and Psyche” (80). This film which exists in three different versions, the longest of which lasts three hours and forty minutes, is an overflowing, romantic and operatic story of love and doom, interrupted by lightnings of passion and sudden visions, embroidered with stylized visuals and surreal exaggerations, a cataract of images, camera movements and double exposures, but also of exquisite landscapes, architectural sights and angles. The story of the film moves over a time span of over one hundred years (beginning before 1800 and ending around 1920), during which the protagonists do not age at all. Behind the narrative line, the European history of the 19th century becomes visible, a process of dissolution and decomposition of the bourgeoisie as well as the nobility. In one scene, a telephone is picked up and from the earpiece a voice can be heard which strongly resembles that of Adolf HITLER.

The film is based upon the verse drama of WEÖRES Sándor, a contemporary Hungarian writer. In “Narcissus and Psyche” private events, excursions into mythology, consideration about aesthetics and the artistic process blend together. The central characters, Narcissus (Laci TOTH) and Psyche (Erzsebet LONYAY), admirably performed by Udo KIER and Patricia ADRIANI, are personifications of mythology from the mythology from the Greek antiquity, they each represent certain positions or psychological patterns: Narcissus is the poet most fond of himself (whose play is only performed in a commercialized version and who ends in misery); Psyche represents the woman and poetess sure of herself, whose life is a succession of stormy adventures, deceptions, fulfilments and renunciations. In his film, BÓDY tries to translate the myth of Narcissus and Psyche into the domains of psychology and history. Science and technology are also introduced into the film by means of visual citations. The film is, as one critic put it, “an essayistic explosion” adorned with a “baroque fireworks of associations”. BÓDY was compared to BUNUEL, FELLINI and also to Werner HERZOG. On account of this film, BÓDY Gábor was called in 1981 “the most extraordinary talent of Hungarian cinema”, “the definite new stylist among Magyar filmmaking newcomers” (Variety). Other remarkable features are the oscillation of the film between a high degree of stylization and the conscious use of “kitsch” as ironic quotation or the use of electronically transformed music.

On account of this film, BÓDY Gábor was called in 1981 “the most extraordinary talent of Hungarian cinema”, “the definite new stylist among Magyar filmmaking newcomers” (Variety). Other remarkable features are the oscillation of the film between a high degree of stylization and the conscious use of “kitsch” as ironic quotation or the use of electronically transformed music.

In Hungary and in Germany, “Narcissus and Psyche” was a success in the movie theatres, the film was even successful – unexpectedly! – as an export product. It received many awards in 1981 and 1982, it was shown in Cannes, Locarno, Berlin and in many other film festivals. In Locarno the film was awarded a bronze leopard for “the successful attempt to introduce image and sound research of experimental cinema into the narrative structure.”

In 1983 BÓDY Gábor made his third film, this time entitled “Dog’s Night Song”. It adopts a burlesque style, the action is set in the present period. Central characters are a false priest (played by BÓDY Gábor himself), an army officer (who develops explosives and chases his escaped wife), an astronomer, a young woman who suffers from lung disease and a communist official. The film is narrated simultaneously in an archaic and a modern style; it aims to convey a picture of “microstructures” within Hungarian everyday life. Some parts of the film were shot in video and in super 8 format; the background music is provided by a Hungarian rock band which also appears in some scenes of the film.

“Dog’s Night Song” is at the same time a play, a formal experiment (although not quite as exuberant as “Narcissus and Psyche”), but also a political and social metaphor, an analysis and criticism of society, expressed by the stylistic means of medieval iconography. The images of the film were shot by the New York camerawoman Johanna HEER, they posses “the ambiguity of magical dream images” (Viper).

The possibilities of the video medium

In the last years of his life, BÓDY Gábor dealt increasingly with the medium of video. He made several experimental shorts in video format, “Der Dämon in Berlin” (The Demon in Berlin, 82) and “Either/Or in Chinatown” (84-85). He lived in Berlin and Vancouver as guest of artists-in-residence programs, taught at the Berlin Film Academy DFFB, gave lectures (about “Total Expanded Cinema”), travelled through various countries with film programs, published video cassettes and books. In 1980, he established “Infermental”, the first international magazine of video cassettes, of which ten series appeared and which was continued and coordinated after his death by his widow Vera BÓDY. He made the film “Mozgástanulmányok 1880–1980” (Studies in Movement 1880–1980) in 1980 as an homage to the American photographer and early film pioneer Eadweard MUYBRIDGE; for television, he filmed “Hamlet” in 1982.

In the last years of his life, BÓDY Gábor dealt increasingly with the medium of video. He made several experimental shorts in video format, “Der Dämon in Berlin” (The Demon in Berlin, 82) and “Either/Or in Chinatown” (84-85). He lived in Berlin and Vancouver as guest of artists-in-residence programs, taught at the Berlin Film Academy DFFB, gave lectures (about “Total Expanded Cinema”), travelled through various countries with film programs, published video cassettes and books. In 1980, he established “Infermental”, the first international magazine of video cassettes, of which ten series appeared and which was continued and coordinated after his death by his widow Vera BÓDY. He made the film “Mozgástanulmányok 1880–1980” (Studies in Movement 1880–1980) in 1980 as an homage to the American photographer and early film pioneer Eadweard MUYBRIDGE; for television, he filmed “Hamlet” in 1982.

Concerning the possibilities of the video medium he said in an interview in 1983: “The invention and introduction of new media like magnetic tape, laser disc and Video contain the possibility to find our way back to a free language of cinematography, to become conscious again of its original possibilities.”

Passion and Spirit

BÓDY Gábor was an unusually warmhearted, open minded person, always bubbling over with ideas and continuously developing new projects. He was able to communicate his enthusiasm to other persons; in this way he exercised a strong influence on his environment and contributed to the development of many artists’ and media groups.  He was a frequent guest of the International Forum of the Berlinale and of the Arsenal cinema in Berlin. He cared personally about the screening of his films and translated “Narcissus and Psyche” (the long version) several times into German through the microphone at the Arsenal because no subtitled print was available at the time.

He was a frequent guest of the International Forum of the Berlinale and of the Arsenal cinema in Berlin. He cared personally about the screening of his films and translated “Narcissus and Psyche” (the long version) several times into German through the microphone at the Arsenal because no subtitled print was available at the time.

His work was always carried forward by passion and spirit, hope and confidence – in the last moments of his life he must have lost this confidence, facing growing difficulties when it came to producing his films and establishing his work center in Hungary. On the 24th of October 1985, he took his own life in Budapest.

The Swiss festival “Viper” (“International Festival for Film, Video and New Media”, originally in Lucerne, now based in Basel) devoted a homage to BÓDY Gábor in 1995; underlining the actuality of BÓDY Gábor’s work in the present time, they wrote: “His theoretical considerations, in view of contemporary debates about digitalization, networks and Multimedia, have acquired new and explosive momentum. His artistic self-conception and his endeavour to find an adequate filmic representation for the complexity of his subjects must be considered an important challenge for many of today’s film and video authors.”

To the question of what he was dreaming, BÓDY Gábor replied: “I am the dream of my life.”